Scripts provide directions on how to behave during the act of protest. We can think of tweets as a type of protest script, communicating narratives, slogans, and actions for online and offline protests. Unlike playscripts that are complete before play rehearsals begin, or traditional social movements where leadership may work backstage to develop scripts before a protest, Twitter scripting happens simultaneous to the performance. Each time an actor interprets a script expressed in a tweet and then performs it by tweeting, retweeting, liking, donating, etc., their action serves as a script for other actors on the platform. It is like a game of virtual “telephone,” with popular interpretations emerging as movement scripts writ large.

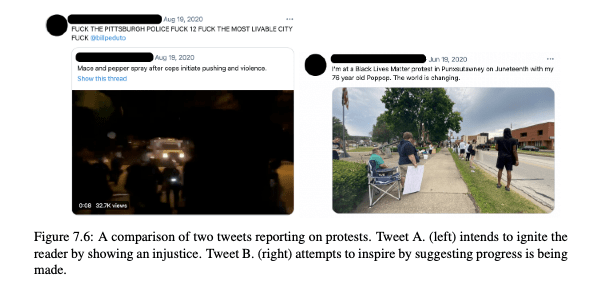

The script coding method I developed in my dissertation draws from Stanislavski’s method of finding an actor’s objective through close reading and script analysis (Stanislavski, 1989). I provided examples of script types and common objectives from the Pittsburgh BLM 2020 dataset, addressing the research questions: What are the characteristics of different script types? And how do scripts explicitly or implicitly communicate instructions for movement participation? I then discuss the potential insights and knowledge contributions that this method of analysis offers, posing questions about the ability of a script to transform an audience member into a movement participant online or off.

One of the strengths of this method of analysis is that the codes can be applied to any networked movement on any social media platform. The transferability of the method and coding scheme makes it ideal for contemporary rhizomatic networked movements which utilize a number of media and communication platforms.

Next I used social network analysis in tandem with dramaturgical analysis to understand

the social drama at the local level, identify primary actors, and gain insight into their scripting processes during three periods of active on-the-ground protests in the summer of 2020. I revealed how actors, script types, and objectives shifted over time to focus on local issues, and how the George Floyd protests intersected with ongoing racial justice movements.

Because objectives are not tied to topics, a major benefit of this method is that it is transferable across movements and can be used to compare different phases of a movement or different factions within it. Together the three scripting types and objectives provide a meso-level of analysis, less specific than topics or content, but providing more nuance than social network analysis alone. While the coding scheme of objectives is likely not a comprehensive list of all objectives present in networked movements, it provides a solid base from which to grow a dictionary.

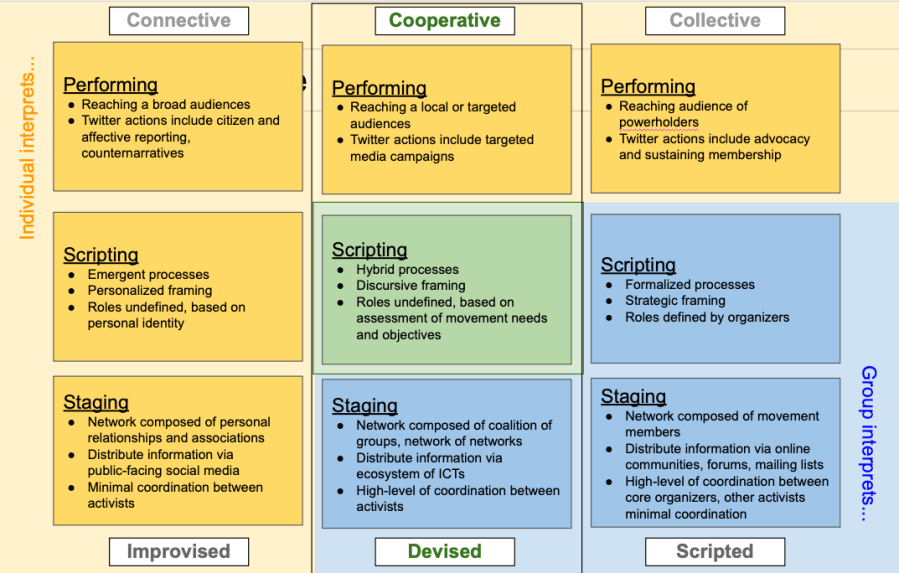

Through dramaturgical analysis, I found two related phenomena that build on existing theory: cooperative action and localization. In Bennett and Segerberg’s ”Logic of Connective Action,” they discuss a continuum from collective action to connective action. Connective action is characterized by the diversity of opinions and approaches within a networked movement and personalized politics, where collective movement identities may be absent, broadly defined, or secondary to other social identities.

Extending the dramaturgical analysis by comparing organizing processes to theatrical scripting processes, between the emergent scripting processes of improvisation and the formalized scripts of traditional theatre, lies the collaborative processes found in devised, community-based and interactive theatre. In a devising process, the script is created collaboratively by a diverse group of theatre artists. Improvisation is often used in this process, allowing actors to contribute to the script, developing their own lines and movements. Individuals lend to scripting processes by offering personal interpretations through scripting and performing, while staging processes are largely negotiated collectively. Devising is very process-oriented, because ultimately staging decisions have to be made and agreed upon by the group in order to execute complex interactions without catastrophe. Once the devising process is established the troupe often repeats it from show to show, tweaking it as they go.

Rather than personalized politics, what I observed in the August Pittsburgh BLM 2020 data was a convergence of scripts and objectives at the community level. A process that I described as “localization.” Especially considering that in May the protests began because of the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, and as the summer progressed, the protests became more focused on local issues and politicians. Although further studies are needed to verify that this a common and generalizable process, localization has the potential to shed light on some of the more mysterious factors of rhizomatic growth in networked movements: how a movement shifts from global outrage to targeted fights for local policy change.